If you’re at all familiar with the alternative wine scene, Konpira Maru wines is probably firmly on your radar.

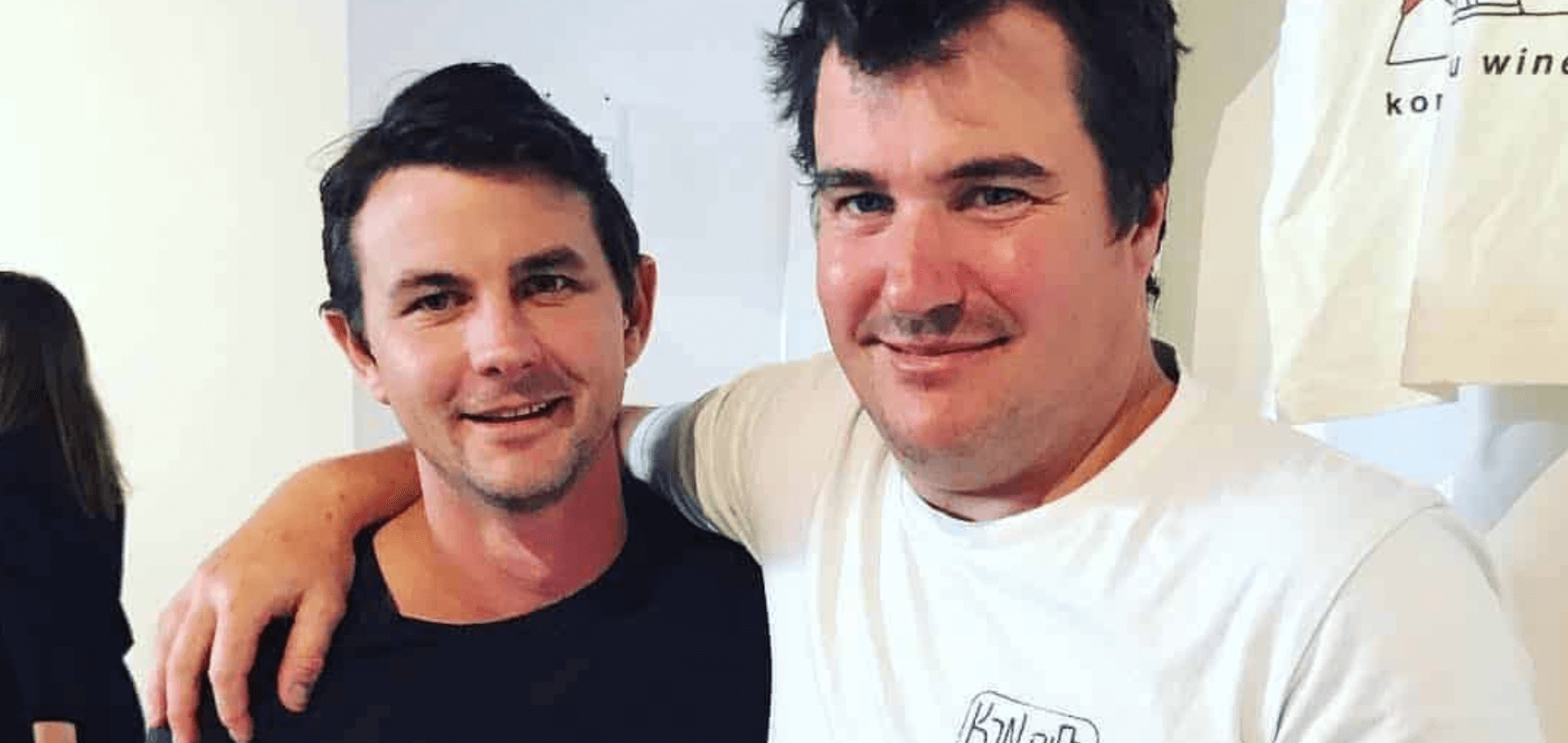

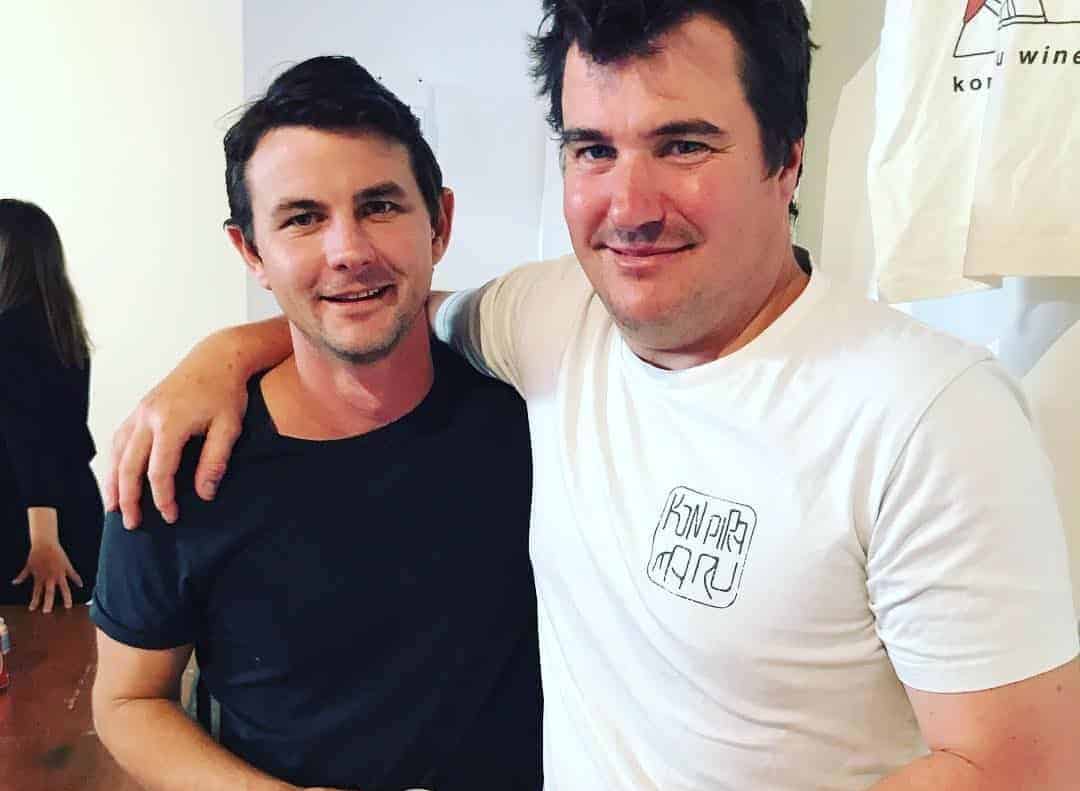

Winemakers, Alastair Reed and Sam Cook are known as much for their down-to-earth approach as they are for their fun, tasty and adventurous wines, and are certainly a force to be reckoned with in the industry.

We sat down with one half of the dynamic winemaking duo, Alastair Reed, to chat about their approach to winemaking and why everyone should support small local businesses.

How was Konpira Maru born?

Al: Our first release was in 2014 with the genesis in mid-2013. Back then, the alternative wine scene was just starting, and Sam and I were discussing how expensive those wines were, making it hard to drink them regularly. Sam was working at Blackhearts and Sparrows in Melbourne and I was teaching winemaking at TAFE. That’s where he and I met. He was my student and tried hard to befriend me in exchange for not failing him. I still failed him mostly.

We were both looking for a creative outlet when we became aware of some grapes being offered up for sale from a vineyard in Merbein (near Mildura) and we snaffled some of their Malvasia, Garganega and Nosiola and made our first two wines, about 500 bottles.

Where do you operate from these days?

Al: Now we make wine from the South Burnett and Granite Belt regions in Queensland as well as Kilmore in Victoria, with the help of our crew of growers. In 2016, we took on our own Whitlands vineyard, sitting high above the King Valley. We farm Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Gris organically here on beautiful red soil, surrounded by sub-alpine Eucalypt forest.

What did you hope to achieve with Konpira Maru?

Al: We set out to make interesting wines with minimal intervention and maximum care. Wines that were full of character, with a focus on affordability and a high-drinkability factor. Our goal was simple – to produce wines we wanted to drink and to inject a little fun into an industry often accused of taking itself too seriously.

What does minimal intervention actually mean?

Al: For us, minimal intervention just means that we don’t intervene if we don’t have to. If you’re a brand that’s producing a million litres of wine, like many of the big wine names are, you really need it to appeal to everyone to get bang for your buck, which means it’s got to appeal to the absolute middle-of-the-road consumers. That usually means you need to load fine wines with chemicals, filter the crap out of them, and add a tonne of preservatives. And more often than not they’re using sub-optimal fruit.

If you buy fruit from caring farmers and you make wines by hand, you don’t need all that extra stuff – you can just let the wine speak for itself.

When is vintage for you?

Al: We make wine in Victoria and in the South Burnett in Queensland, which is an awesome little region, but harvest is quite early on in the year. And we also make wine in Victoria, in two extremely cool climate regions – Whitlands and around the town of Kilmore. That means we’re harvesting in Queensland January through April and in March through June in Victoria, which means we effectively have a six month vintage, which is pretty unusual.

How does the timing and location impact the wines you produce?

Al: It means that we can produce a range of different styles and also hit the market at different times.

What’s different about the way you approach wine?

Al: Like a lot of our mates in the industry, we create a handmade product. Unfortunately, the traditional Australian wine industry has become focused on large-scale quantities and automation of absolutely everything. This isn’t ideal, because the retail machine gears itself around these big conglomerates and what they’re producing, which can affect the quality of the product. And so, an industry that used to be embedded and supportive of local communities, has moved to a model that’s all about reducing employment, reducing costs, having massive fulfilment centres, and bringing less people into the industry.

A good example is Wolf Blass in the Barossa, which is marketed around the larger-than-life character of Wolf Blass himself and how he built his company, but at the end of the day it’s part of a multinational behemoth that has a fully automated fulfilment centre outside the Barossa where everything’s done by machines. From our perspective, that’s reducing the size of the wine industry, and leading to an eventual homogenisation of it, which serves no one. We’re all about producing good-value, interesting products and working with as many different small businesses as possible in order to create a product that has some substance to it.

How do you do that?

Al: It’s all about people and the relationships you build. We’re on a first-name basis with every single person involved in getting our wines made. This is a great position to be in because you can see the other businesses grow as well, and a community develops around your product.

How do you grow as a business?

Al: It doesn’t matter how good the internet of things is, or the internet itself for that matter, you can only get so big before you start to compromise on what’s important to you. For us, it’s all about offering a value proposition to the customer, where they might pay a little bit more to get a bit more. The success of our business has really come down to that; our customers are willing to pay for a quality product that’s been made with care, and because of that, everyone can get a slice of the pie.

So, who’s involved in bringing a Konpira Maru wine to life?

Al: So many people, from truck drivers to farmers to designers. We work with small growers in small towns, so for our wines made out of Kilmore, for example, we buy grapes from a guy there, the bloke who drives the truck is in Yarra Glen, the bottles comes from a family owned business in Perth, the caps come from a small business in Moorabbin, our labels come from a family owned printing company in Thomastown and are designed by a young guy on the Sunny Coast, who happens to be one of our best mates, and one of our biggest retailers is Blackhearts & Sparrows – a brother-and-sister-owned small business, made up of a number of excellent independent wine stores in Melbourne and Canberra.

So it takes a village.

And how much are you involved in actually creating the wine itself?

Al: We’re completely involved in every aspect. For example, we run a vineyard in the small area of Whitlands, in partnership with Jim Hardie. We prune the vineyard in winter in the snow and we do that with a lovely Thai family who’ve lived in the King Valley for nearly 20 years. And then the grapes have bud bursts in October and the grapes grow among the wombats and the kangaroos. The grapes grow and then it’s all about fostering a healthy understory of grasses and trying to get rid of weeds.

And then we harvest with our families and make all the wine – all pressed, fermented, bottled, within 20 metres from the vines themselves.

How is the Queensland experience different?

Al: In Queensland, it’s quite difficult to make wine. Everything up there is done quite rudimentarily – it’s much more rustic winemaking. We’ve got one tiny little pump and liquid transfers are done by hand. It’s also about three and a half hours in the truck from Brisbane and then you have to truck stuff out, so everything takes a bit longer. Because everything’s done by hand there, though, we can get away with using absolutely no sulphur, because you can really control the amount of oxygen pick up.

Is sustainable the same as organic when it comes to winemaking?

Al: Nope. We use all organic sprays for disease control, where required, purchased from a small guy in Benalla, but in Whitlands, for example, we also farm our grapes sustainably, which goes beyond organic farming, because it means we’re actually trying to function an ecosystem – a practice that Jim Hardie helped pioneer.

Why should people get behind small, local businesses?

Al: When you buy something from a small-medium producer you’re going to get something interesting. You might not always love everything, but that’s ok. If your aim is to satisfy absolutely everybody, you’ve got to take the middle road – you can’t have extremes. So you end up with this beige result, which everybody likes a little bit. We’re not interested in that. A product from our business is a hand-made product that’s made with care. It’s not made to satisfy a focus group and it’s certainly not going to be boring.

News you care about. Tips you can use.

Everything your business needs to grow, delivered straight to your inbox.